Alpha CubeSat

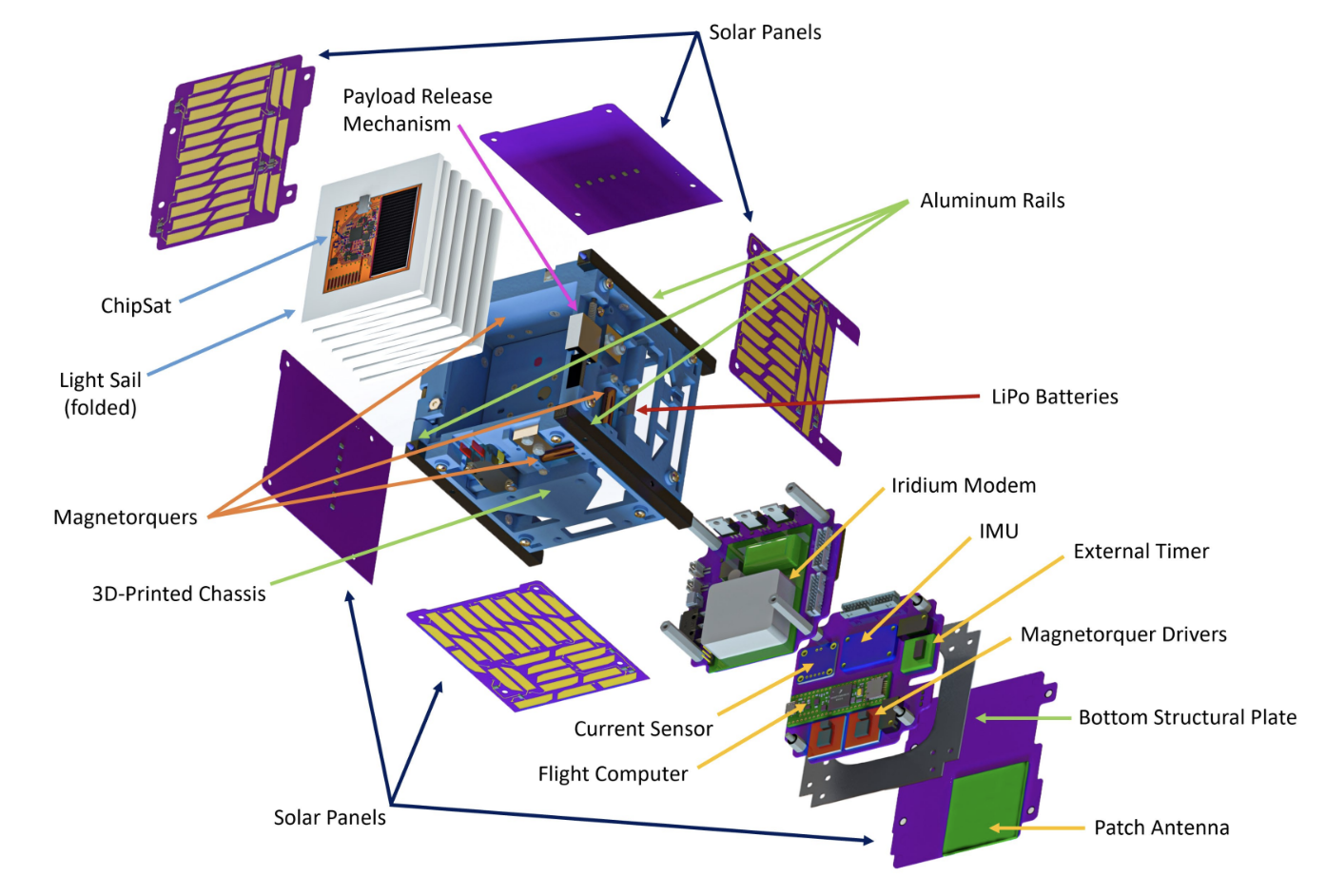

A 1U cubesat deploying from the ISS which aims to release an ultralight light sail as part of NASA's CubeSat Launch Initiative

In fall 2022, I joined the Space Systems Design Studio (SSDS) at Cornell, where I am working on the Alpha CubeSat project. As part of NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative, the Alpha CubeSat mission aims to launch a 1U CubeSat from the International Space Station to verify the performance of a highly retro-reflective material for light-sail propulsion.

As someone who had close to no knowledge about CubeSats prior to SSDS, I was drawn by the opportunity to try working in a field that I had never tried before. Not to mention that working with space related things is just awesome!

During my time at SSDS, I mainly worked on 3 projects: developing the flight software for the 4 ChipSats which will be attached to the light sail, testing the CubeSat’s flight software, and rewriting/developing the CubeSat ground station software.

In addition to software projects, I also worked in the cleanroom to help assemble the flight version of the CubeSat!

ChipSat Flight Software

Working with another member on the team, I developed the ChipSat’s flight software (FSW), which is responsible for reading data from the 5 main sensors (IMU, accelerometer, magnetometer, temperature, and GPS) and using the LoRa radio to downlink them to TinyGS, a worldwide network of 1000+ LoRa ground stations. This was done using a combination of C++, Arduino, and PlatformIO.

As my first deep dive into embedded programming, I faced many unique challenges along the way. The development of ChipSat FSW involved many aspects of embedded software design. This included designing new features under the constraints of the ChipSat’s hardware, dealing with the challenges of interfacing with avionics sensors, and developing effective debugging strategies. The process of finalizing the downlink packet, designing the randomized downlink algorithm (to prevent collisions between ChipSats), and creating the GPS boot (power-saving) mode are good examples of how radio transmission as well as power constraints led to trade-offs which influenced the final design. These trade-offs, such as balancing the precision of data sent in downlinks, the frequency of downlinks, and the importance of different sensor data are decisions which are unique to embedded software design. Additionally, working on the GPS NMEA message parser was a good example of the challenges of working and debugging with avionics hardware. The limited flash and RAM size constraints drove me to create code that was as simple as possible, leading me to initially turn to writing a custom GPS parser instead of using a library. Then, the shortcomings of that code, a buffer overflow which was caused by the high rate of corrupted GPS messages, lead me to develop effective debugging strategies for embedded programming, such as evaluating the RAM and power usage as well as narrowing down the root cause using serial prints. While I wished that I had initially designed the GPS parser to be more robust, I feel like this was a valuable lesson that led me to gain a lot of intuition for debugging embedded systems, something which will certainly be useful in the future.

For more technical details about my work, you can view my semester report and the GitHub repository.

CubeSat Flight Software

My work on the CubeSat’s FSW mainly consisted of running hardware-in-the-loop (HITL) tests on the FlatSat, which is a 1:1 replica of the CubeSat’s electrical system, except that it is laid out on a breadboard to allow for easier testing. These tests usually involved entering edge cases that could be encountered in orbit (ex. sensor failures, no radio signal, stuck door) and verifying that the software could handle these and still successfully deploy. Since most of the codebase was written before I joined, this was a unique experience as every failed test run allowed me to dive into the codebase to attempt to find flaws, which was a surprisingly effective way of understanding what the code did.

CubeSat Ground Station

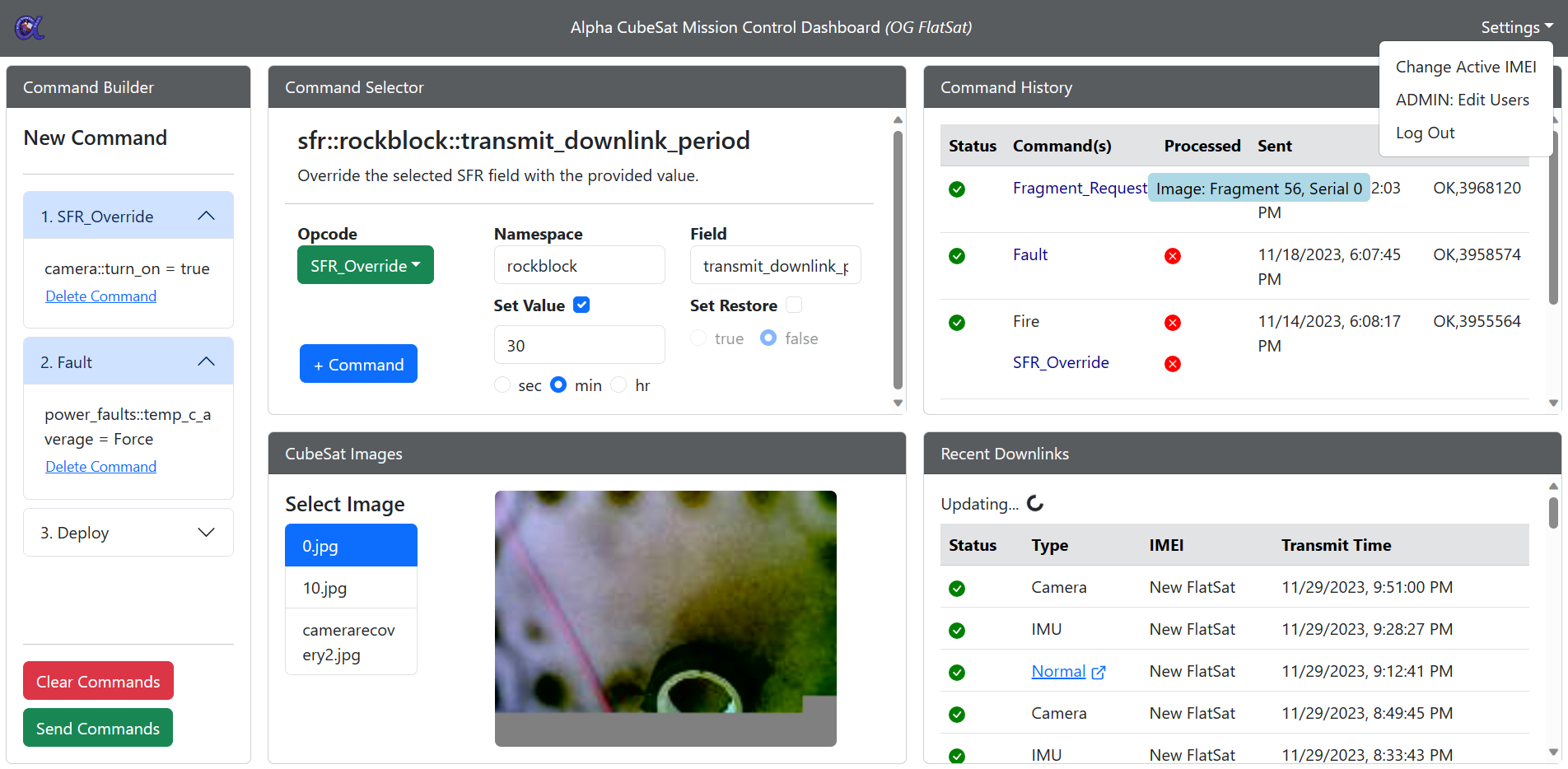

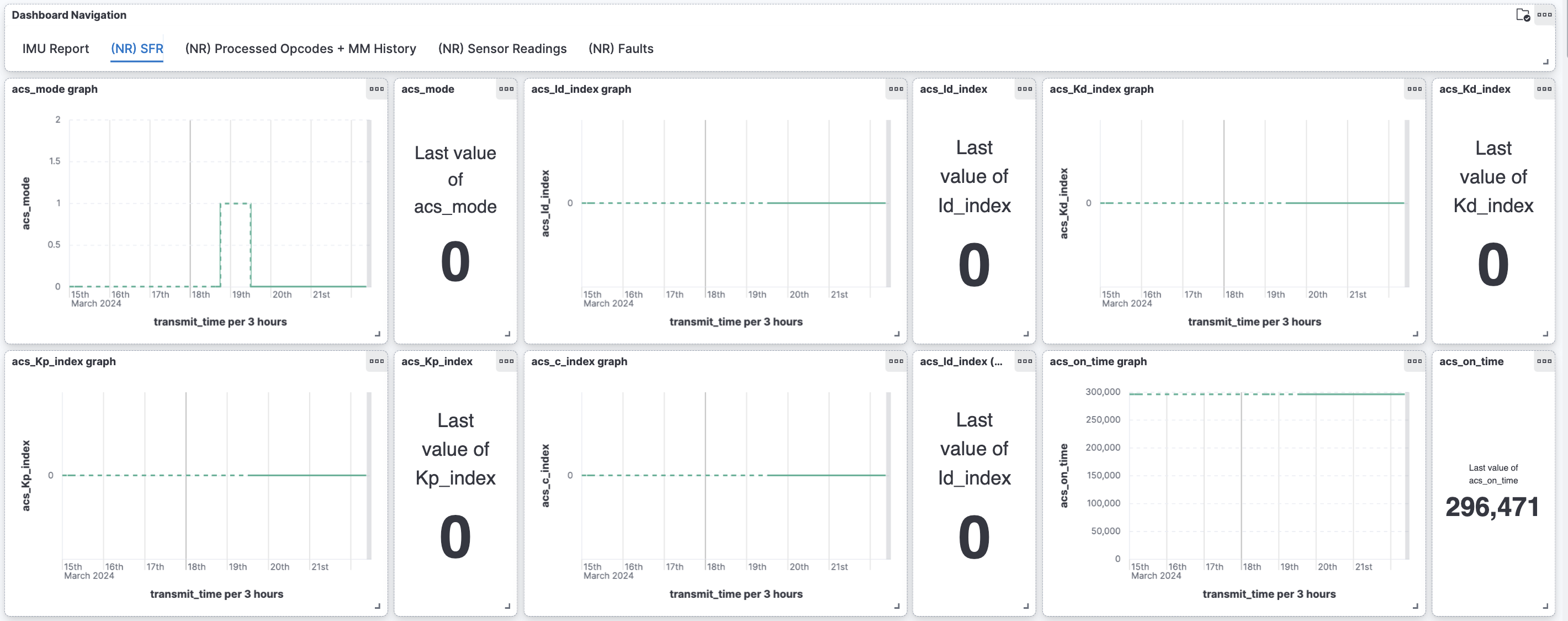

Working with another member on the team, I worked on redesigning as well as continually developing the CubeSat’s ground station software. It is designed as a full stack web app with a Flask backend and a React frontend. We also utilize Elasticsearch and Kibana to visualize mission data. The GitHub repository is available here.

More specifically:

- Flask backend: Parses raw telemetry reports received from the RockBlock API and sends it to ElasticSearch. Also handles command processing, authentication, and user management through a REST API.

- React frontend: Simple and intuitive dashboard to send commands, view downlinked images, and view the most recently sent commands and received downlinks

- Elasticsearch: Stores the CubeSat’s downlinks after they have been processed by the backend

- Kibana: Used to create dashboards and graphs to visualize the telemetry data in Elasticsearch

Shortly after joining the Alpha project, I learned that a barebones ground station had been implemented in the Clojure functional programming language over the last few semesters. As a niche language, Clojure did have some minor benefits. However, its high learning curve and hard to read syntax made it hard to maintain. As a result, one of my first tasks was the rewrite the backend using Python and the frontend using React. By the end of the semester, running a lines of code analysis showed that the new codebase was roughly 30% smaller!

Following the completion of the rewrite, I worked closely with the flight software team to determine what changes needed to be made to the ground station to best support the mission. Changes include allowing multiple commands to be sent at once, a drag/drop system to reorder commands, abstracting the UI to make it easier to support new commands, revamping the token-based login system, adding a user management system for admins, support for sending commands to multiple CubeSats (helpful for testing), and adding recent downlink widget. Besides creating Kibana dashboards to help mission operators to visualize the incoming telemetry data, I also played an important role in deploying the ground station, gaining experience in Linux, Nginx, and cybersecurity. The ground station’s architecture is shown below. Green arrows show the path of telemetry data, red arrows show the path of commands, and black arrows correspond to user actions.

CubeSat Pictures